This blog is our project for our research writing class at Emerson College. It is a comprehensive site dedicated to information about the desegregation of schools in the Boston area, and the incidents and information surrounding busing within the Boston Public School Systems.

A book by Michael Patrick MacDonald.

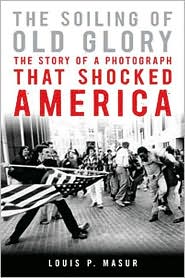

A book by Michael Patrick MacDonald. Book by Louis P. Masur

Book by Louis P. Masur"Sometimes a moment can change history. This one took 1/250th of a second.

The photograph strikes us with visceral force, even years after the instant it captured. A white man, rage written on his face, lunges to spear a black man who is being held by another white. The assailant’s weapon is the American flag. Boston, April 5, 1976: As the city simmered with racial tension over forced school busing, newsman Stanley Forman hurried to City Hall to photograph that day’s protest, arriving just in time to snap the image that his editor would title “The Soiling of Old Glory.” The photo made headlines across the U.S. and won Forman his second Pulitzer Prize. It shocked Boston, and America: Racial strife had not only not ended with the 1960s, it was alive and well in the cradle of liberty.

Louis P. Masur’s evocative “biography of a photograph” unpacks this arresting image in a tour de force of historical writing. He examines the power of photography and the meaning of the flag, asking why this one picture had so much impact. Most poignantly, Masur recreates the moment and its aftermath, drawing on extensive interviews with Forman and the figures in the photo to reveal not just how the incident happened, but how it changed the lives of the men in it. The Soiling of Old Glory, like the photograph it is named for, offers a dramatic window onto the turbulence of the 1970s and race relations in America."

A book by Susan E. Eaton.

A book by Susan E. Eaton. A book by Ronald P. Formisano.

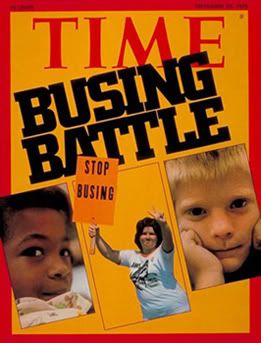

A book by Ronald P. Formisano. Time Magazine covered the busing crisis extensively in several issues of the magazine. The magazine cover shown above is from a 1975 issue, although the coverage started as early as September of 1965 with this article, an interview with Louise Day Hicks. In the interview, Hicks states that she feels that busing will not solve problems with education. Instead, she proposes "compensatory education" in which students get more "individualized attention" and "remedial instruction."

Time Magazine covered the busing crisis extensively in several issues of the magazine. The magazine cover shown above is from a 1975 issue, although the coverage started as early as September of 1965 with this article, an interview with Louise Day Hicks. In the interview, Hicks states that she feels that busing will not solve problems with education. Instead, she proposes "compensatory education" in which students get more "individualized attention" and "remedial instruction."

Young Caucasian students protest the arrival of African-American students during the early days of busing.

Young Caucasian students protest the arrival of African-American students during the early days of busing.

"People feel very strongly about these issues. They're entitled to their views."

"[I am] dismayed by the President's completely inappropriate and insensitive remarks about the school situation in Boston...the President is entitled to his own view about the issue, but the timing of today's remarks can only give aid to those who would flout the decision at this difficult time for our city."

"Can anyone believe that people using or condoning acts of violence as well as vulgar racial epithets are making a democratic protest against busing? No. They are making a un-democratic assault on equality."

Before student protestors went out to City Hall Plaza, they gathered in city council chambers. There, Louise Day Hicks served the students hot chocolate and led them in the pledge of allegiance, depicted here.

Before student protestors went out to City Hall Plaza, they gathered in city council chambers. There, Louise Day Hicks served the students hot chocolate and led them in the pledge of allegiance, depicted here.

Photo by Stanley J. Forman depicting Joseph Rakes, a 17-year-old South Boston Teen, attacking Theodore Landsmark, a lawyer, with an American flag at a rally at City Hall Plaza on April 5, 1976.

Photo by Stanley J. Forman depicting Joseph Rakes, a 17-year-old South Boston Teen, attacking Theodore Landsmark, a lawyer, with an American flag at a rally at City Hall Plaza on April 5, 1976.